How to transport heavy loads over bridges

FEATURE

FEATURE

When transporting these loads on public roads, there is a level of risk that needs to be carefully managed. There are physical obstructions to consider en route, such as overpasses, bridges, lights, power lines, and underground lines.

There are also road regulations that vary in countries, states and at local levels, which address the maximum trailer loads, maximum loads per axle, tire sizes, and the length and width of a transport permissible. This is to ensure the safe transport of a load and prevent any damage to road infrastructure.

Every transport is different and changing road regulations, routes, and load dimensions require different transport solutions. Conventional trailers and self-propelled modular transporters (SPMTs) are both safe and efficient transport methods for these projects.

Operator-controlled SPMTs may only reach speeds of 5 km per hour but offer significant capacity, control, leveling abilities, and a wide range of movement options. Multiple prime movers and mechanically driven modular trailers can also be combined to push-pull loads at a greater speed.

When hauling heavier loads, the starting principle is to add more axle lines to create longer trailers with more tires on the road.

This increases capacity and spreads the weight of the load, reducing the amount of pressure each tire exerts on the road.

A trailer with more axle lines can carry a greater load whilst remaining within the required axle and tire loading, staying within road regulations, and preventing any damage to road surfaces.

The value of this was demonstrated when Mammoet developed a custom 22-axle trailer to transport a Cat 797 dump truck for a customer in the mining sector in Canada.

At 15 m long, 10 m wide, and 363t, large items like this often must be disassembled and transported in pieces, then reassembled after delivery, but transporting the truck fully assembled saved around six days of downtime. Of course, close attention must also be paid to the intended transportation route; specifically, whether road curves or inclines will prevent passage.

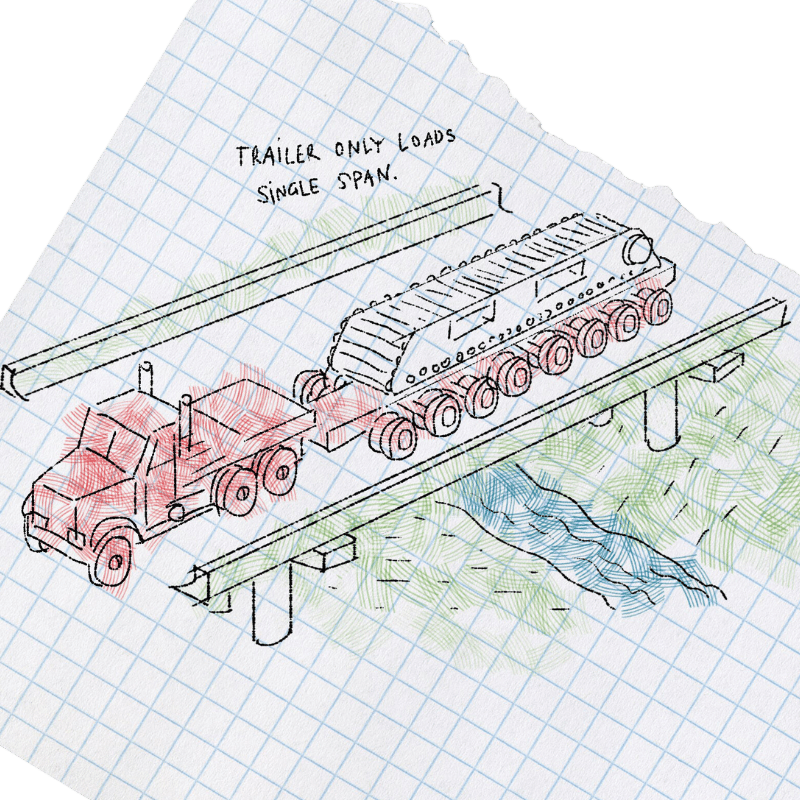

Adding more axles doesn’t always meet the regulatory or licensing requirements though. Designed for general traffic, bridges have a certain life expectancy and safety margin.

They are usually built with concrete or steel beams running in a longitudinal direction with the traffic. Typically, one lane of the road will be carried by one or two bridge beams. At a certain point, too many axles will overload a bridge beam because they are too concentrated in one area over a span.

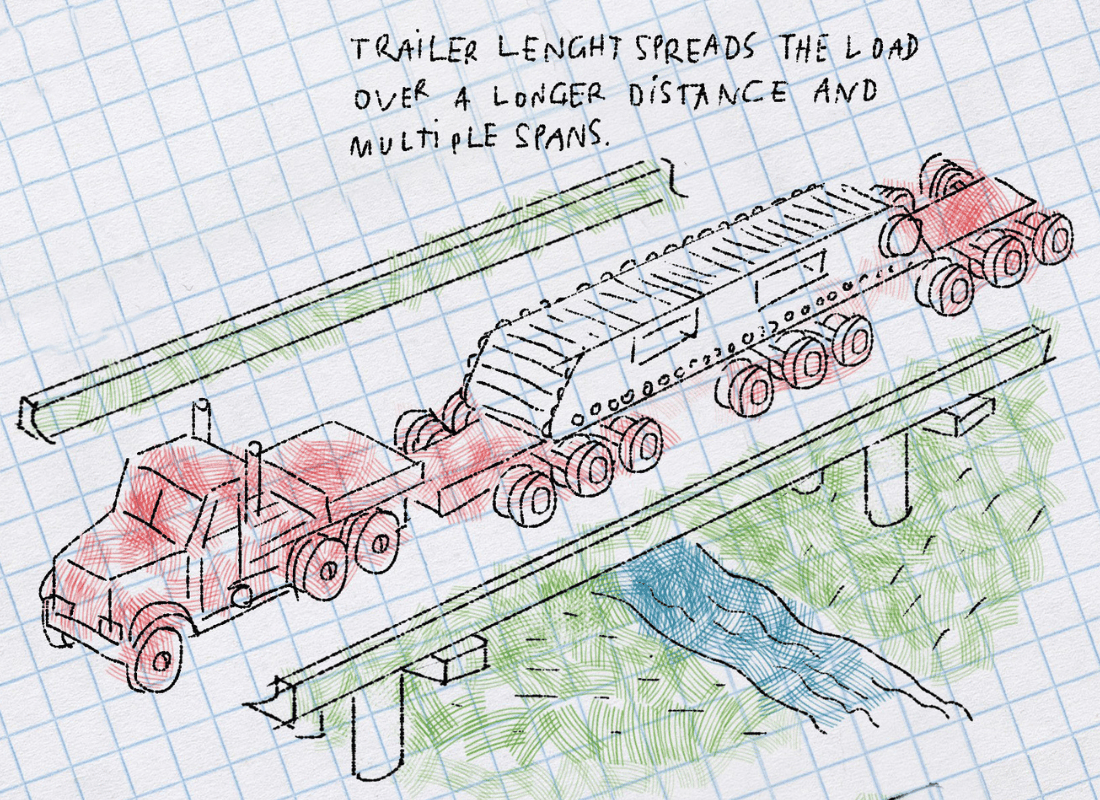

When hauling large loads over bridges, you can extend the trailer, so the weight is spread over a greater distance, and therefore more bridge spans. We do this by creating spaces between the axles, in effect extending the trailer length and spreading the load over a longer section of the bridge.

This allows the weight per axle to be increased and increases the overall payload capacity. In the case of non-extendable trailers, spacers can be added between axles for the same results.

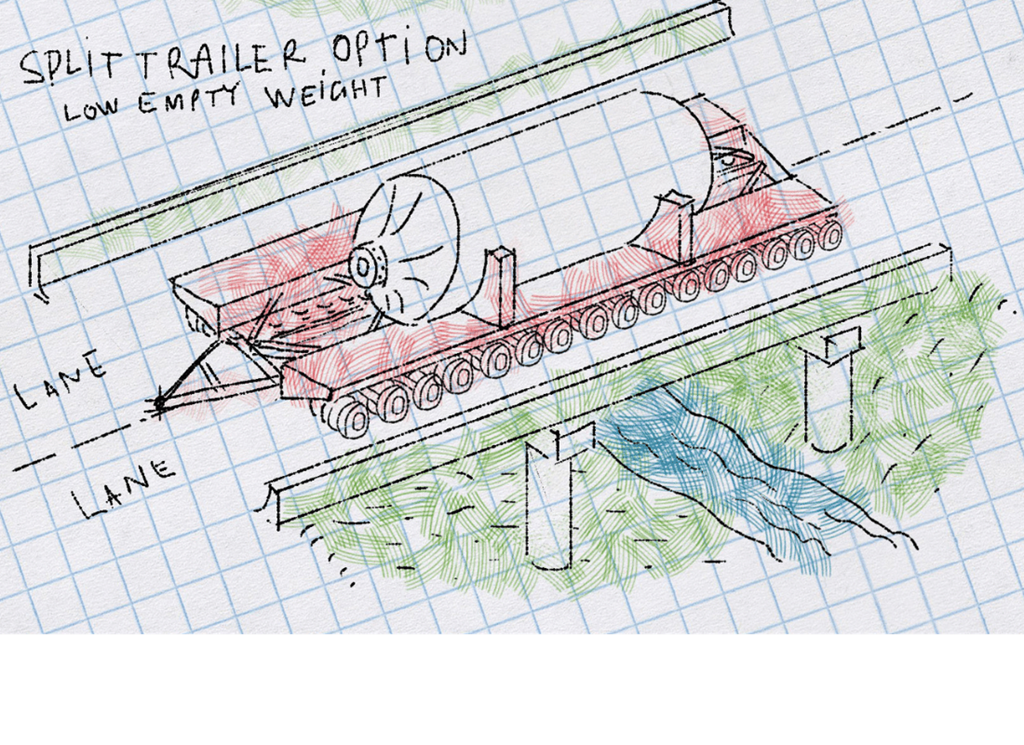

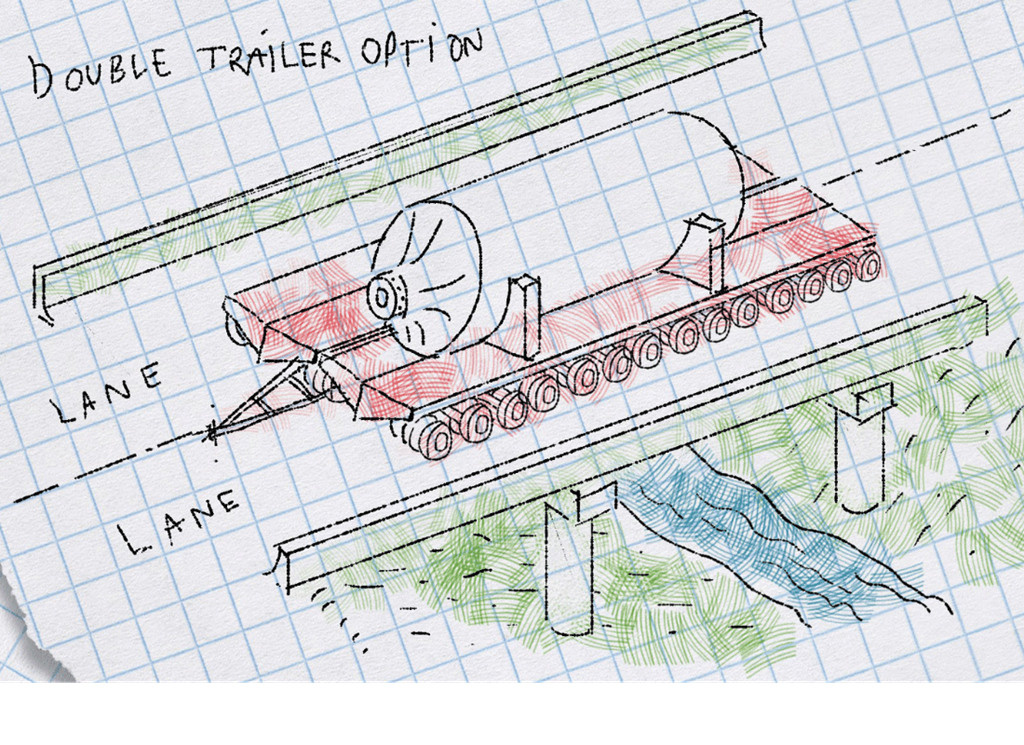

If transporting heavier or oversized loads that cannot be accommodated by one lane, two trailers can be connected side by side, thus using two lanes of the bridge and distributing the weight over additional beams.

Improving on this concept further, a split trailer provides the same or more stability through a wide loading platform over two lanes of the bridge. As the name suggests, this is a single trailer that is split down the middle and connected only with beams. The gap between the trailers reduces the overall trailer weight, which increases the payload capacity.

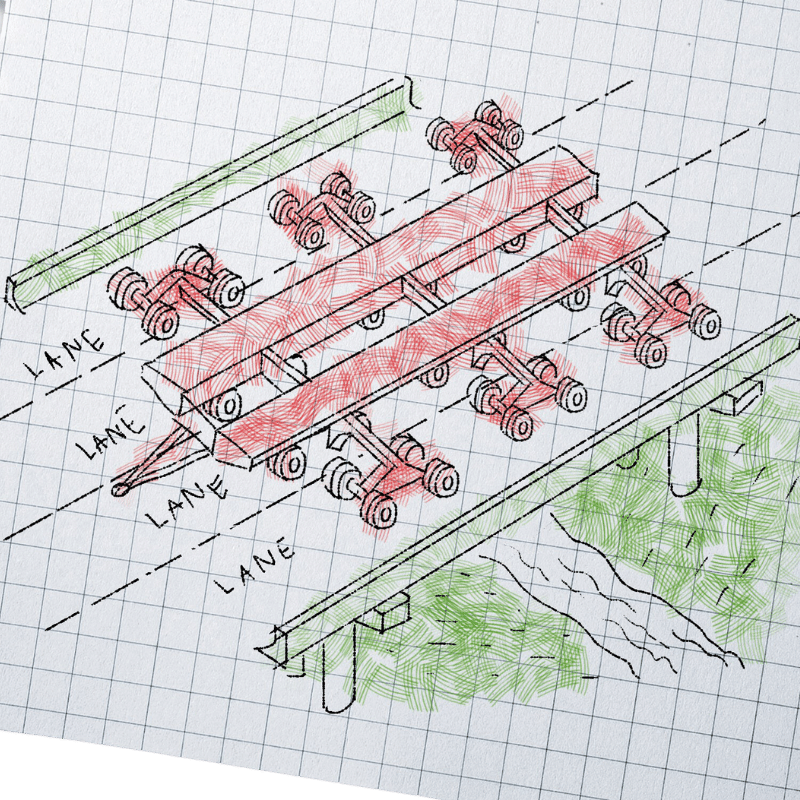

When hauling even larger loads, axles can be added on the outside of a split trailer. These additional wheels are called dollies.

This solution uses the entire bridge width (four lanes) and spreads the load over all the bridge spans. Once the bridge has been crossed, the dollies can be removed and the connection beams will fold in line with the trailer, reducing the width to two lanes.

Everything we have learned from different trailer configurations can also be applied to SPMTs. They are modular and can be connected to a higher cumulative capacity. However, in many cases, the increased load and axle capacity that comes with the additional units are not required.

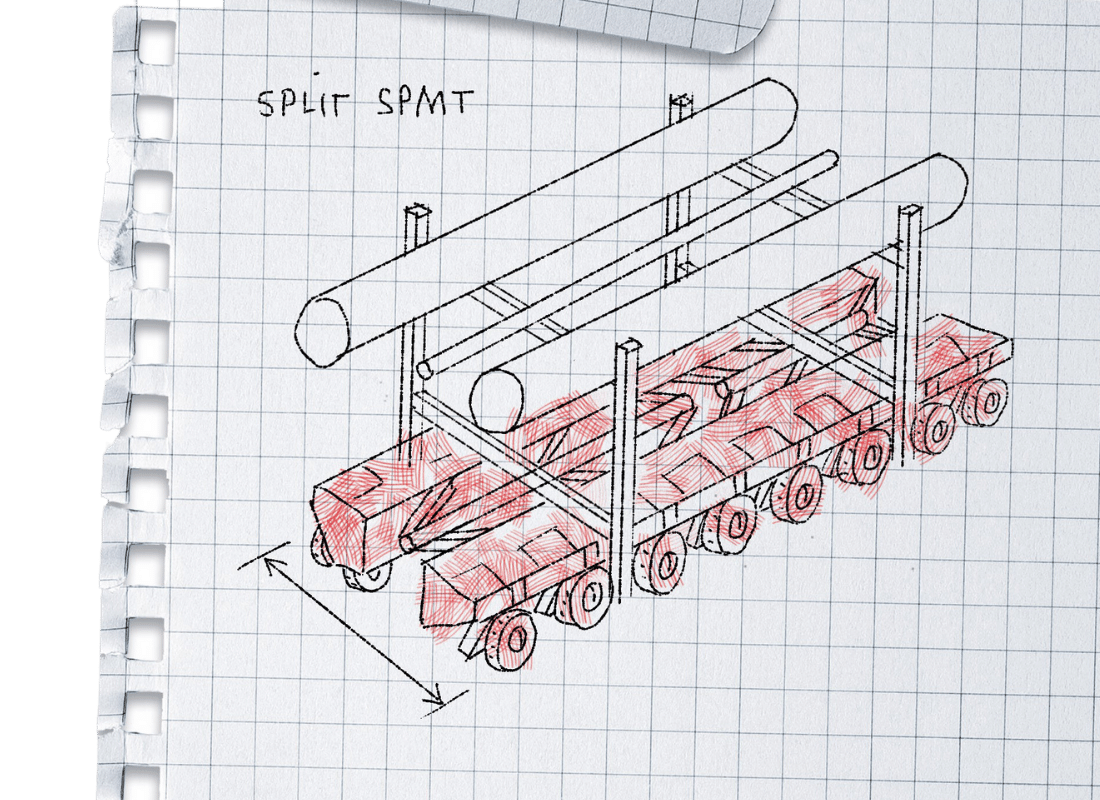

Similar to the split conventional trailer, split SPMTs offer the same amount of capacity as a single SPMT, but the trailer will have the same or more stability as a double combination - with less empty weight. Building on this, Mammoet has developed a patented widening adaptor that increases the track width of a split SPMT – thereby increasing the width of the loading platform at flexible intervals.

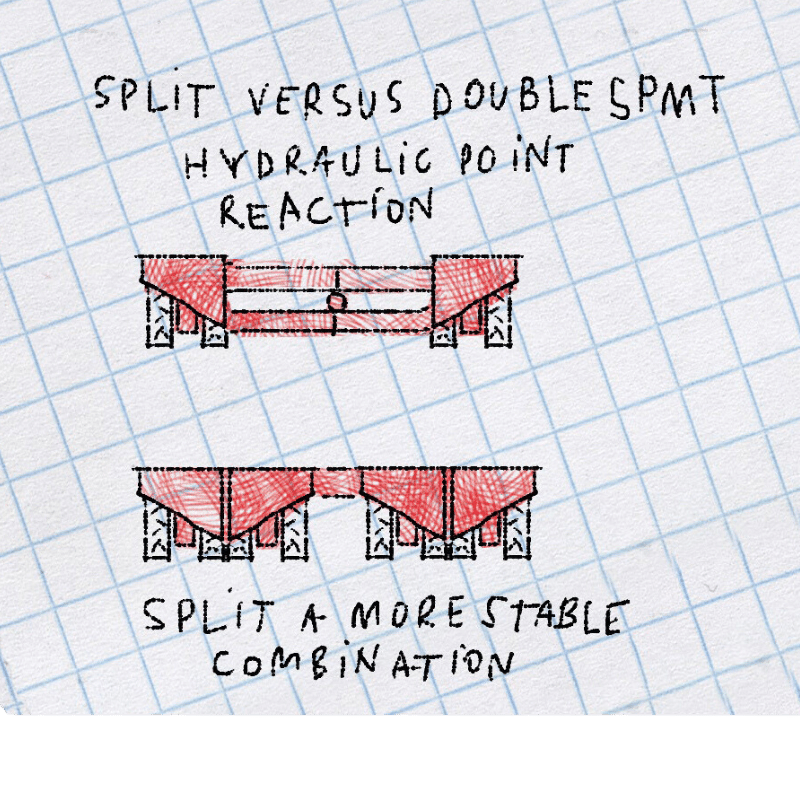

One of the greatest advantages of using a split trailer and split SPMT combination is the added stability. The hydraulic points are created by the axles: the further the axles are from the center, the greater the stability.

On a split SPMT, these are further apart than on a single or double trailer, and the load is spread across the greater width between the axles. This makes split SPMT combinations ideal for transporting moderate loads with a high center of gravity.

High and wide loads with a high center of gravity – such as large pipe rack modules - are typically transported on multiple rows of SPMTs placed side by side. Currently, additional trailers are required to support the length and width of the load; ensuring its safety and stability.

This is where split SPMTs and the widening adaptor can provide advantages, offering the same loading deck space and an increase in the stability of the load. An added advantage is that the width of the SPMT with the spacer adaptor is now variable from 2.43 m to 6.30 m.

The split SPMTs combined with the adaptor enable safer and more cost-effective transport of loads and reduce the carbon footprint of transports that would otherwise need more SPMT units. Its adjustability also allows trailers to maneuver between street furniture, such as concrete pedestals.