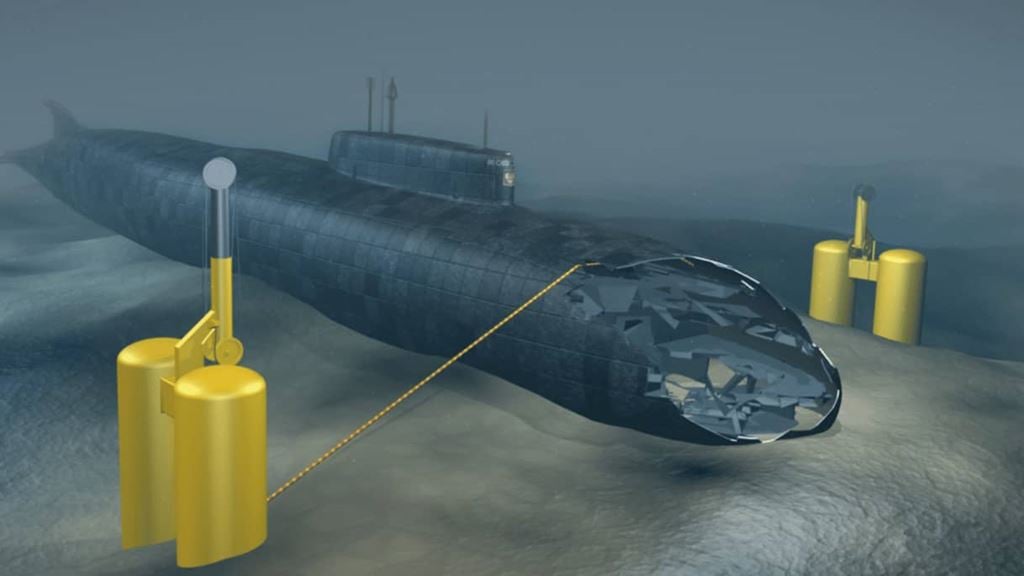

Consisting of a steel thread with a specially processed buffer, the cutting wire was positioned between two suction anchors and moved hydraulically between the anchors as they sucked themselves deeper into the seabed.

Meanwhile, in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, another team began to prepare an enormous barge with the lifting equipment needed to raise the remainder of the submarine. 26 strand jacks, each with a hydraulic lifting capacity of 900 ton, were assembled on the Giant 4 barge. Each strand jack was fitted with purpose-built grippers, attached to 200-kilometer cables, wound around purpose-built steel wheels. Each gripper would be inserted through a small hole and then opened to fix to the surrounding area, providing a strong anchor to the vessel. The strand jacks would then be used to synchronize all points of contact, compensating to ensure a level and controlled rise.

The 130-meter semi-submersible barge was specially adapted for use. A large hole was cut in the hull and large saddles constructed under the barge to transport the precious cargo underneath, with the Kursk’s command tower protruding into the hull.